What is a public syllabus?

Or, first of all, what is a syllabus, period?

What, then, is a public syllabus (also referred to sometimes as a crowdsourced syllabus or a hashtag syllabus)?

- A new, still emerging genre of online writing. This means that its genre conventions and rhetorical features are still very much unsettled and up in the air.

Earliest forms of it (consider this in terms of exigence):

- #Fergusonsyllabus

- Emerged in response to the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO on August 9, 2014

- Began as an attempt for educators (teachers, professors) to crowdsource and gather sources and readings for the coming semester (Fall 2014) in order to discuss the shooting and its aftermath in a productive and intelligent way. “This just happened, and there’s a lot we need to talk about with it (students will be expecting us to talk about it)–how the hell are we supposed to teach it?” >> http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/08/how-to-teach-kids-about-whats-happening-in-ferguson/379049/

- Multiple target audiences, though: educators targeting other educators, but also–by virtue of this syllabus’s publicness–educators targeting a more general audience of internet users. Performative, in that respect: a conversation among educators intended to influence the broader conversation about this issue by virtue of being intentionally “overheard” on Twitter

- #Charlestonsyllabus

- Emerged in response to the shooting of African American churchgoers by a white supremacist in South Carolina on June 17, 2015

- http://www.aaihs.org/resources/charlestonsyllabus/

- http://www.ugapress.org/index.php/books/charleston_syllabus/

- Consider again the multiple exigences here, tied to multiple target audiences: https://books.google.com/books?id=Lr4tDAAAQBAJ&lpg=PA3&ots=iyWvxE3Nl3&dq=%22inspired%20by%20the%20%23FergusonSyllabus%20and%20eager%22&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q=%22in%20thinking%20about%20events%20in%20charleston&f=false. How do we teach this, but also, how can we influence (and edify or enrich) the broader American conversation about this?

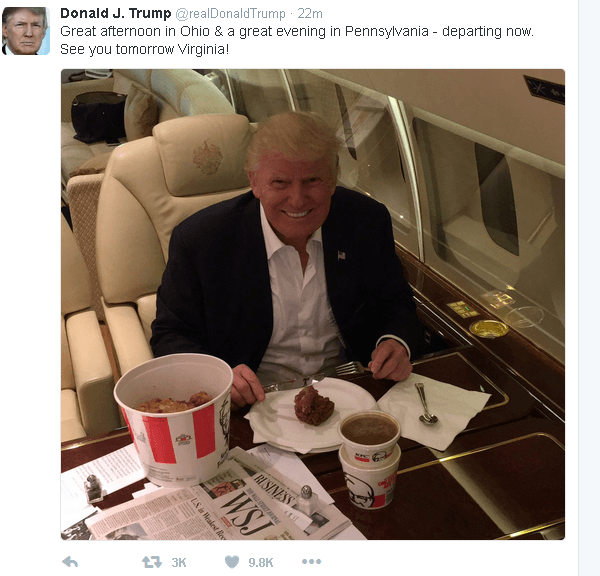

This brings us to the two Trump syllabi.

- “Trump 101” (http://www.chronicle.com/article/Trump-Syllabus/236824)

- D.B. Connolly and Keisha N. Blain, “An Introduction To Trump Syllabus 2.0” (http://www.aaihs.org/an-introduction-to-trump-syllabus-2-0/)

- D.B. Connolly and Keisha N. Blain, “Trump Syllabus 2.0” (http://www.publicbooks.org/feature/trump-syllabus-20)

Trump Syllabus 2.0 is interesting not only for its stated criticisms of the Trump 1.0 syllabus, but also for the more implicit ways in which it refines and improves this still emerging genre of writing as a whole.

- Distinguishes between primary and secondary sources

- Includes potential “assignments”